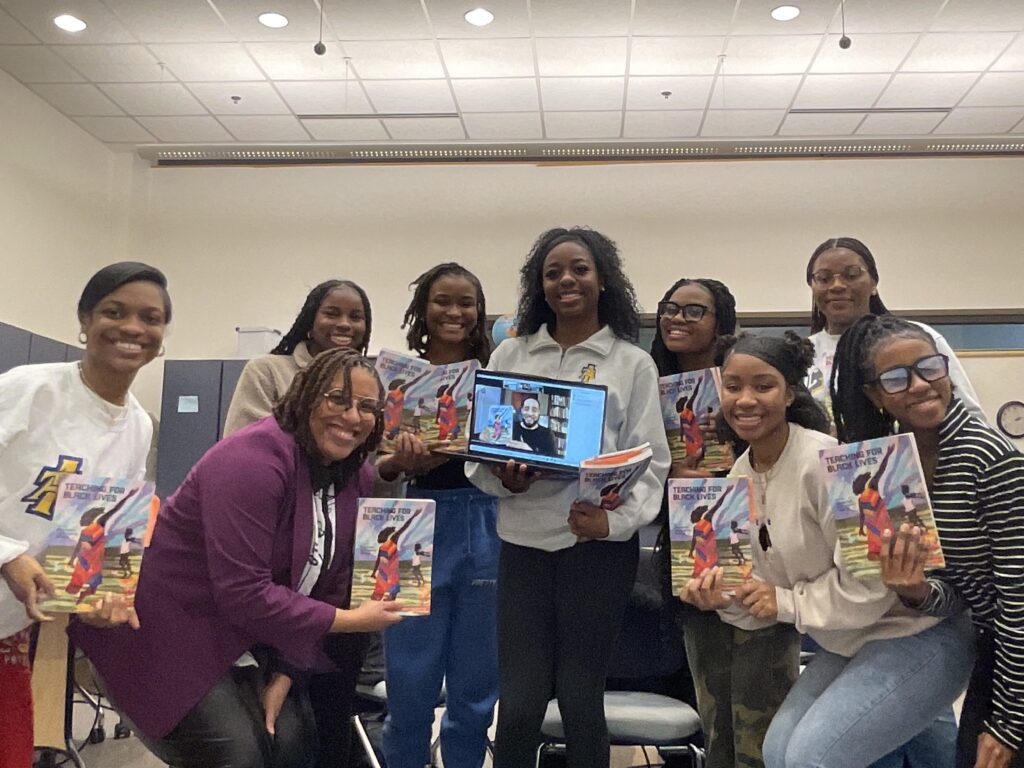

Greensboro T4BL Study Group Members

Study group members trickled in, grabbed a chair, and warmly greeted each other as they joined the circle. The room echoed with laughter as folks settled in and caught up with each other at the end of the school day. Twenty teacher educators and pre-service teachers from North Carolina A&T State University gathered for their monthly Teaching for Black Lives study group meeting. Jesse Hagopian, Teaching for Black Lives co-editor, and Julia Salcedo, study groups administrator, visited the group virtually.

After a quick check-in, Charnell Long, assistant professor of Science Education and study group coordinator, listed suggested readings from Teaching for Black Lives that had been of interest and asked the group to decide what they’d like to read and discuss that day. Members selected “How K–12 Schools Push Out Black Girls: An interview with Monique W. Couvson” (p. 251). Long gave the group time to read and then invited folks to share their thoughts.

One participant said,

Reading “How K–12 Schools Push Out Black Girls” made me think of the first time I got pulled over because of my lights. I was 16 and I didn’t pull over when he wanted me to so he ended up putting me in handcuffs. I was scared to death. I called my grandma on my airpod. I was crying. I couldn’t even talk to the officer. He eventually talked to my grandma and she explained that I was just scared and he left before my parents got there. Reading about these experiences happening in school, I’m happy that I didn’t have that experience.

Long asked, “Would you classify your school as urban, rural, suburban?”

She responded that she lived in a suburban area outside of the city where she went to school and remembers a diverse student population.

Long said,

I taught in all Black schools and sometimes class comes into play. Your own class in a Black space can save you and people who are considered of the lower class are the ones experiencing it. As Couvson talks about the “good girls,” you’re either “good” or “ghetto”. So in some ways you were probably classified as “good” and then some girls at your school were classified as the “ghetto girls.” They probably experienced a lot of what they’re talking about here.

Another participant said,

It was interesting to me when they were talking about dress code. I went to an all-white school. Basically you couldn’t wear crop tops in June but people would still do it, white girls especially and nobody would say anything. If a Black girl was wearing it, it was automatically, “Oh, no, you can’t wear that. You have to put on a big long shirt. It’s inappropriate.” The same rules didn’t apply to everybody.

Another member shared their experience attending an urban charter school. She said,

We had a uniform and you would think that stops the policing of Black bodies but there were subtle anti-Black rules that I remember talking to my friends about. Our earrings couldn’t be bigger than a quarter. We couldn’t have more than two bracelets. Our hair couldn’t be different colors. It was telling me that they care more about how you look than being in the classroom or not. At one point in my school we were being taken out of class because we didn’t have white socks. I was like, “Is my education more important than how I look?”

All of the members of the group are Black women, and it seemed they could all share several stories about the negative comments they heard or received about how they dressed or accessorized in school. Long affirmed the group’s sentiment that dress codes are definitely not equally applied.

One member said she was shocked by Couvson’s response to the question, “What do you believe are the biggest issues facing K–12 Black female students?” on p. 253:

You get cases like a 6-year-old girl having a tantrum in her kindergarten class and instead of her being engaged with love or responded to with some degree of caring, she is placed in handcuffs in the backseat of a police car.

Several members voiced how awful this young girl was treated.

“Isn’t it normal for a 6-year-old to have a tantrum? You don’t put them in handcuffs!”

“That must’ve been so scary.”

A member said,

I think that’s why we need more people like us in the classroom. We know what that feels like and other teachers don’t. They can only hear our experiences. Even being in the classroom — and not just for Black students, but for other students of color — I feel like it’s a safer space because you understand that they all have different needs.

“My issue is, how do we go from classroom to handcuffs? You’re telling me not one of the teachers can deescalate the situation? You have to call the police?” said another participant.

Long responded,

It demonstrates how they saw the Black child’s behavior and the criminalization over time. As Black people we see the humanity in each other. Most of us do. We need more Black teachers but we need more conscious Black teachers. You don’t want Black teachers who are extensions of the machine — extensions of white supremacy. We need an advocate for Black students.

Hagopian thanked everyone for the lively discussion and powerful stories they shared. He proceeded to share his own story:

I started my teaching career in an elementary school in Washington, D.C. We had a teacher who wouldn’t call the office if they had a student who was being disruptive, they called 911 and the police would come straight to the classroom. One time the cop had a 4th grader up against the wall, their feet dangling and screaming in his face. This is unfortunately an everyday trauma that our kids are facing and we have to design a different education system that’s about caring, nurturing, and healing trauma — not about punishing. That’s what we’re fighting to try to change.

Sometimes what we call bad behavior is actually resistance to racism. If you’re in class and the teacher is not teaching you about yourself and your culture, then when you check out and you’re playing around, that gets labeled as, “You don’t care about your education.” But maybe that teacher doesn’t care about your education and you’re resisting. Then you get sent to the office and labeled “bad” and you get swept up by the school-to-prison pipeline that’s designed to push you out.

We need curriculum that engages Black kids, that helps them understand their own power so they’re focused on their learning because it’s helping them get somewhere they want to go.

The Teaching for Black Lives study groups are a critical starting point to allow educators to reflect on their own schooling experiences, imagine new possibilities, and work toward positive outcomes.